The Development of East Boston

A Kaleidoscope of Change

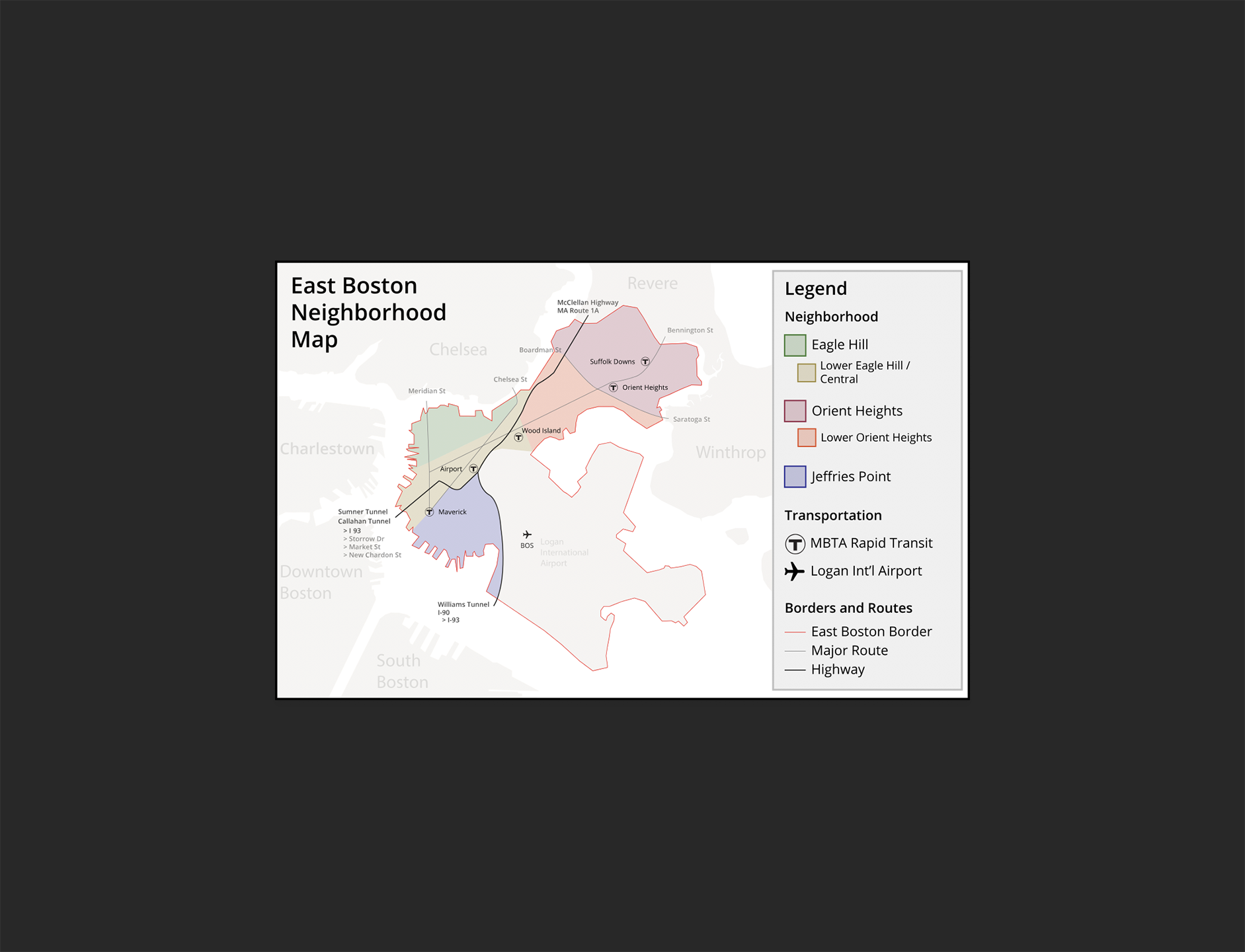

For generations, East Boston, or "Eastie", has been a gateway neighborhood for new immigrants in search of the economic and educational opportunities available in the Greater Boston region. Though the source countries of immigration have changed, the deep bonds of a tight knit community have remained. As a marginalized neighborhood of the city and home to Logan Airport, East Boston has fought hard to maintain its essential character.

This project presents a select number of stakeholder views on East Boston’s current real estate development boom.

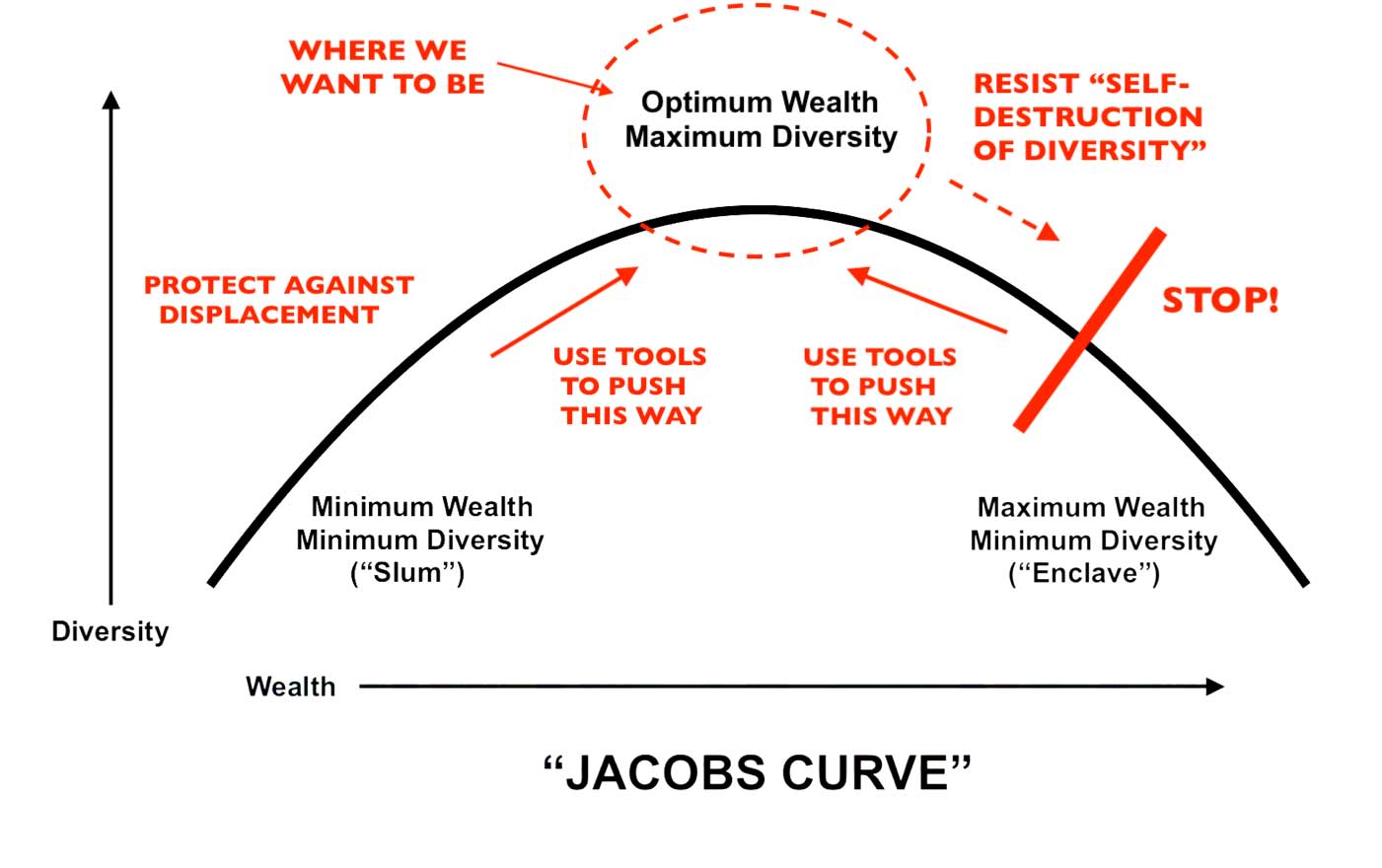

Is gentrification a positive or negative force?

Maverick Square is safer, and the parks and walkways are cleaner. But longtime elderly and poor residents are being evicted with no place to go.

What is the optimal solution for all and is it achievable in East Boston?

Diagram by Michael Mehaffy via CNU Public Square. [ https://www.cnu.org/publicsquare/]

Diagram by Michael Mehaffy via CNU Public Square. [ https://www.cnu.org/publicsquare/]

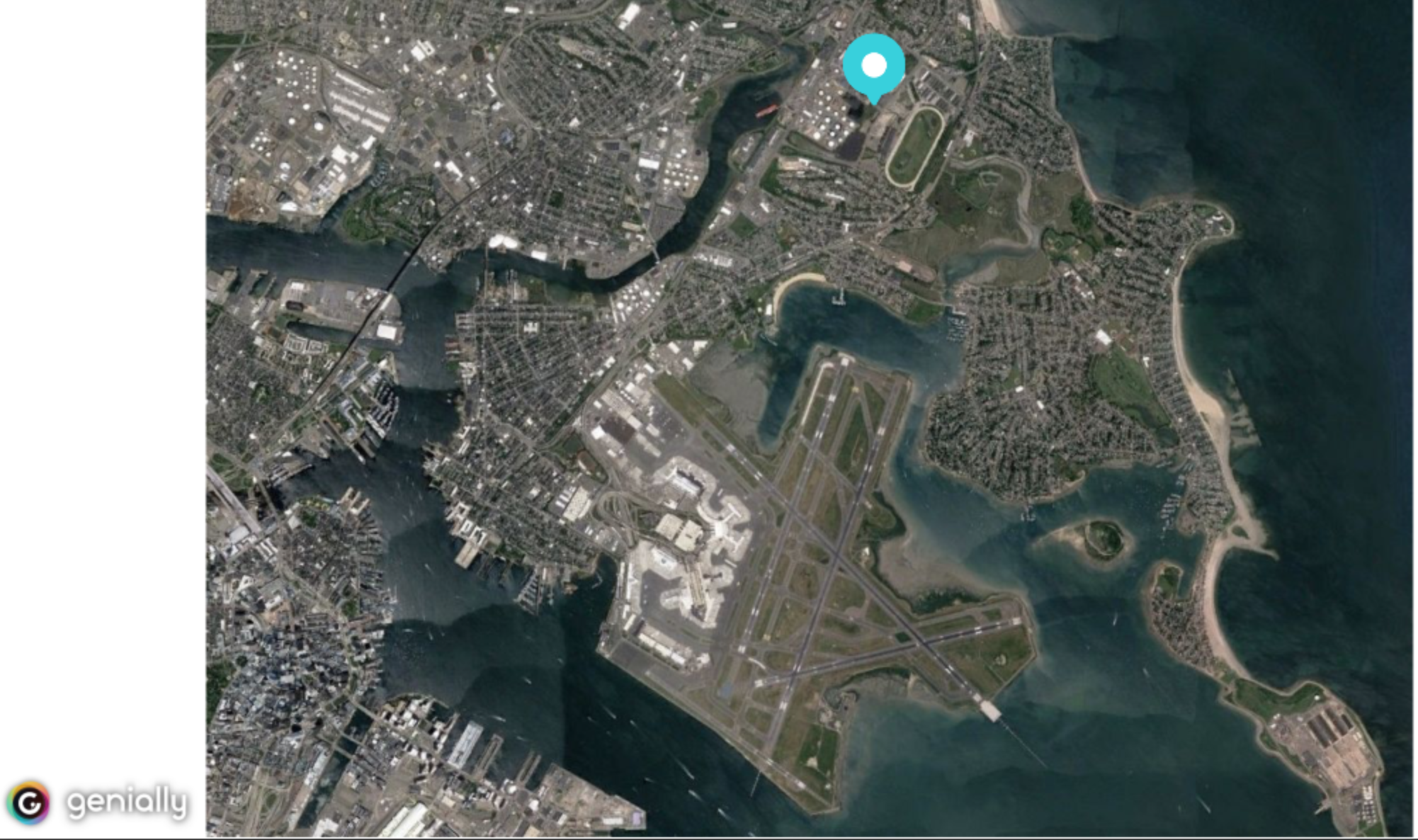

THE BIG PICTURE

In our reporting, we discovered there are no generalized answers. It all depends on who you ask and what is their individual point of view.

One of the only sure things about cities is that they are forever changing. Some regenerate while others deteriorate. Some grow in population while others shrink. Some are facing floods and fires while others remain untouched.

Boston is no exception. From 1950-1980, Boston’s population decreased 30% from 801,444 to 562,994, in large part due to a post-war shift to suburban living. Beginning in 1980, the trend reversed. By the 2010 US Census, the population of Boston had grown to 617,594, an almost 10% increase from its lowest point. [1] According to the World Population Review, Boston’s estimated population in the 2020 Census will reach around 780,000 to 790,000.

It has also set in motion a housing crisis. With a shift in the flow of affluent residents from the suburbs into the city, property prices and rents have skyrocketed.

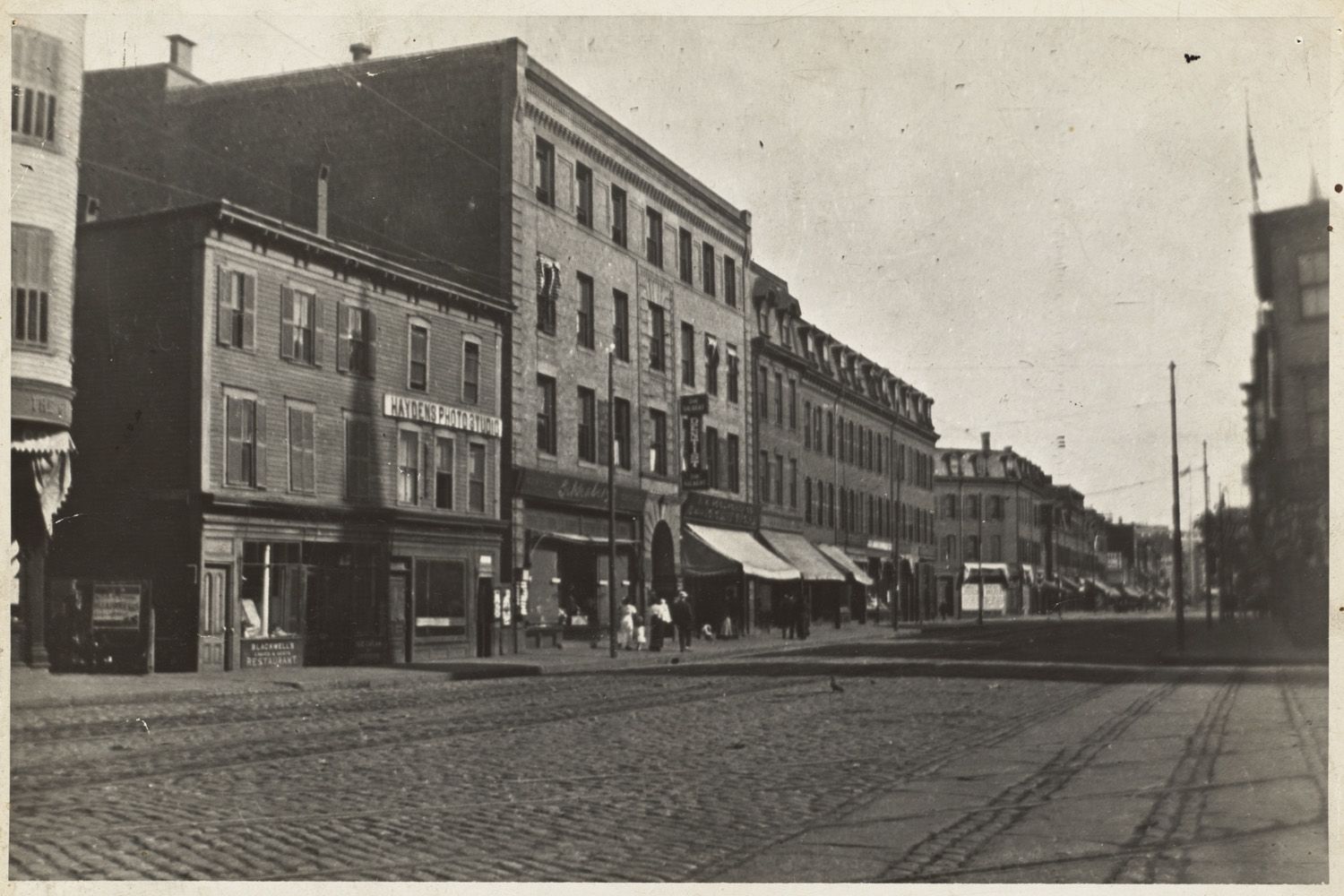

Bennington Street at Day Square - Boston Public Library

Bennington Street at Day Square - Boston Public Library

Meriden Street at Central Square - Boston Public Library

Meriden Street at Central Square - Boston Public Library

Commonwealth (Logan) Airport - Boston Public Library

Commonwealth (Logan) Airport - Boston Public Library

Saratoga Street - Boston Public Library

Saratoga Street - Boston Public Library

POV: Annabel Rodriguez

First Generation Striver

Annabel Rodriguez’s story embodies the American dream. In 2005, her Dominican born father brought the family from New York to East Boston.

“He moved here first because he thought it would be a better life for us,” said Rodriguez. “The rent was cheap, there were lots of jobs, and the schools were great.”

Though Rodriguez still considers herself a New Yorker, she and her family grew to love East Boston and here she found great success. She graduated from East Boston High in 2009, Boston University in 2013, and Suffolk Law School in 2016. By September 2018, with two prestigious law clerkships on her resume, Rodriguez was hired by McDermott, Will & Emery, one of Boston’s top tier law firms.

With her increased salary, Rodriguez and her family moved from their original two-bedroom apartment on Eagle Hill to a newer three-bedroom apartment in Orient Heights.

She has witnessed the economic changes in East Boston over the past 14 years and well recognizes the advantages and disadvantages of the growth. The arrival of new shops and restaurants catering to young professionals who have moved into waterfront condos has also brought the displacement of high school friends and their families who are not earning enough to remain.

As a young attorney who is from East Boston, Rodriguez feels ambivalence as she straddles two worlds. She enjoys the influx of other young professionals and the opportunity to socialize in her city. Likewise, Rodriguez appreciates the improvement in community services, specifically the renovation of the East Boston Neighborhood Health Center in Maverick Square.

Yet she is also frustrated by the long lines at the supermarkets where shelves can empty out by mid-day. And she hopes that the Blue Line will be extended towards Revere, that there is a plan to mitigate the increase in cars and congestion.

Rodriguez believes that it is only fair that current residents – especially those living in affordable housing units - benefit in some way from the infusion of wealth.

Even Rodriguez worries about the pace of growth in East Boston. If housing costs continue to rise at the current pace, will she and her family be able to purchase property?

“My goal is to buy a place where me, my mother, and brother, if he wants to, can live together,” says Rodriguez. “I want to make sure that my mother can retire and not have to work.”

With two and three family homes selling for a million dollars, Rodriguez is keenly aware of the burden of taking on the debt. She hopes that she can make it work so that one day, she can raise her own family in East Boston.

POV: Margaret Farmer

Community Leader

Margaret Farmer did not expect to like East Boston when she agreed to look at an apartment in 2004. But as she walked onto the block and she saw all the families, she felt a deep sense of community. Upon seeing a beautiful and spacious apartment, she agreed to rent it before even learning the monthly price.

The neighborhood, however, was not as eager to have her as she was to join.

“For the first few years that I lived here, nobody would talk to me, because I was a renter,” said Farmer. “They all figured I was going to leave.”

It took three years for her neighbors to open up. And then one day she got a notice in her doorway about a development project that was unfolding just down the street. Unfamiliar with the practice of community activism, Farmer was perplexed about why she’d been included.

“But, I thought, well, if I'm getting this, it must be important,” said Farmer. “And so I went to the meeting. And it turned out to be for the local neighborhood association, which I didn't even know existed.”

There began a classic entrée into the essential character of East Boston. A place with a deep sense of ownership that is well organized to protect its residents and the status quo as needed. In 2011, Farmer ran for and won a leadership position on her neighborhood association. She has been actively involved in everything from economic planning boards to a local nonprofit that converts unused areas into small farms around East Boston.

“I am so glad I moved to East Boston all those years ago,” said Farmer.

Farmer’s investment in this community has given her an understanding of Eastie’s uniqueness among Boston’s neighborhoods. It’s where cultural and economic diversity blend to create a rich social tapestry where neighbors look out for each other.

She is very worried that the development of the luxury housing market is threatening this essential character.

Like Annabel Rodriguez, Farmer has observed the displacement of longtime residents of East Boston and knows that the implications of being forced from your home go much beyond a temporary disruption in daily commutes or in finding an alternative market for food.

“We've seen a large percentage of the population that's had to move to Chelsea, Lynn, and Lawrence,” said Farmer. “And that safety net that they had here, being surrounded by people they knew in a community they knew, is slowly disappearing. It affects them in other negative ways.”

It tears apart the social connections that are integral to individual health and well-being.

Farmer believes there are mechanisms available to force a real estate developer to invest into the neighborhoods that are being so profoundly and negatively impacted .

Though Margaret Farmer does not worry about her own housing stability at the moment, she is very worried about the changes unfolding around her.

“My biggest fear is that we [will] no longer be a neighborhood that cares about one another, and become one that only cares about ourselves,” said Farmer. “One of the great things about living here in East Boston is that there is a collection of activists and people in the community who are going to show up, who are going to write letters who are going to scream at public officials...nicely.”

She has learned that this is how citizens make public officials aware when they've made a mistake. Examples abound, such as the Greenway.

“It was because 30 years ago, residents saw that they did not have enough green space and said, ‘that's not acceptable.’”

Farmer wants people to understand that when new residents move into a neighborhood without a sense of ownership and long-term investment, life on the ground is simply diminished.

POV: Councilor Lydia Edwards

Advocate for her community

Boston Councilor Lydia Edwards is not opposed to development nor to change. She is opposed to “building without intention.” Intentional building is when the ultimate goal of your planning process is to preserve a neighborhood of mixed income families.

“True neighborhoods have folks with a lot of means and folks without as many means, but they're talking and getting to know each other,” said Edwards on a tour of the Maverick Square area. “I think it's important for kids who don't have a lot of money to go to school with kids and families that do. And for them to see the humanity in each other.”

A product of thoughtful community-centered building practice is Maverick Landing. Completed in 2006, the 396-unit property includes a variety of rental and owner-occupied units that promote community and connection among residents. The project was recognized as a sterling example of innovation and leadership in the building of much needed affordable housing.[1]

The spate of luxury towers that have been built in the last decade along the East Boston waterfront – with several more in development currently -- are in figurative and literal opposition to Edwards' vision. Built to block out Maverick Landing's view of the water, these properties' target market is affluent young professionals or empty nesters, most of whom will be White.

Edwards’ has worked as a legal services attorney, inside of Boston City government, and now as an elected official whose job it is to advocate for the interests of her constituents. These experiences inform her view that the creation of a “sub-neighborhood” on the waterfront, with its own grocery store and access to public transportation, is no accident.

When you intentionally put these units where you do and you concentrate these units where you have, what does it say about what the waterfront is for everybody else, who has views and access to it in a different way?” said Edwards.

Councilor Edwards finds herself in the trenches of Boston’s real estate development fight at a time of significant change in the composition of city (and state) government. In the period since the last Boston real estate boom, prior to the 2008 Great Recession, the Boston City Council has changed dramatically. What was an almost exclusively white, male group of elected officials, it is now comprised of fifty percent women of color.

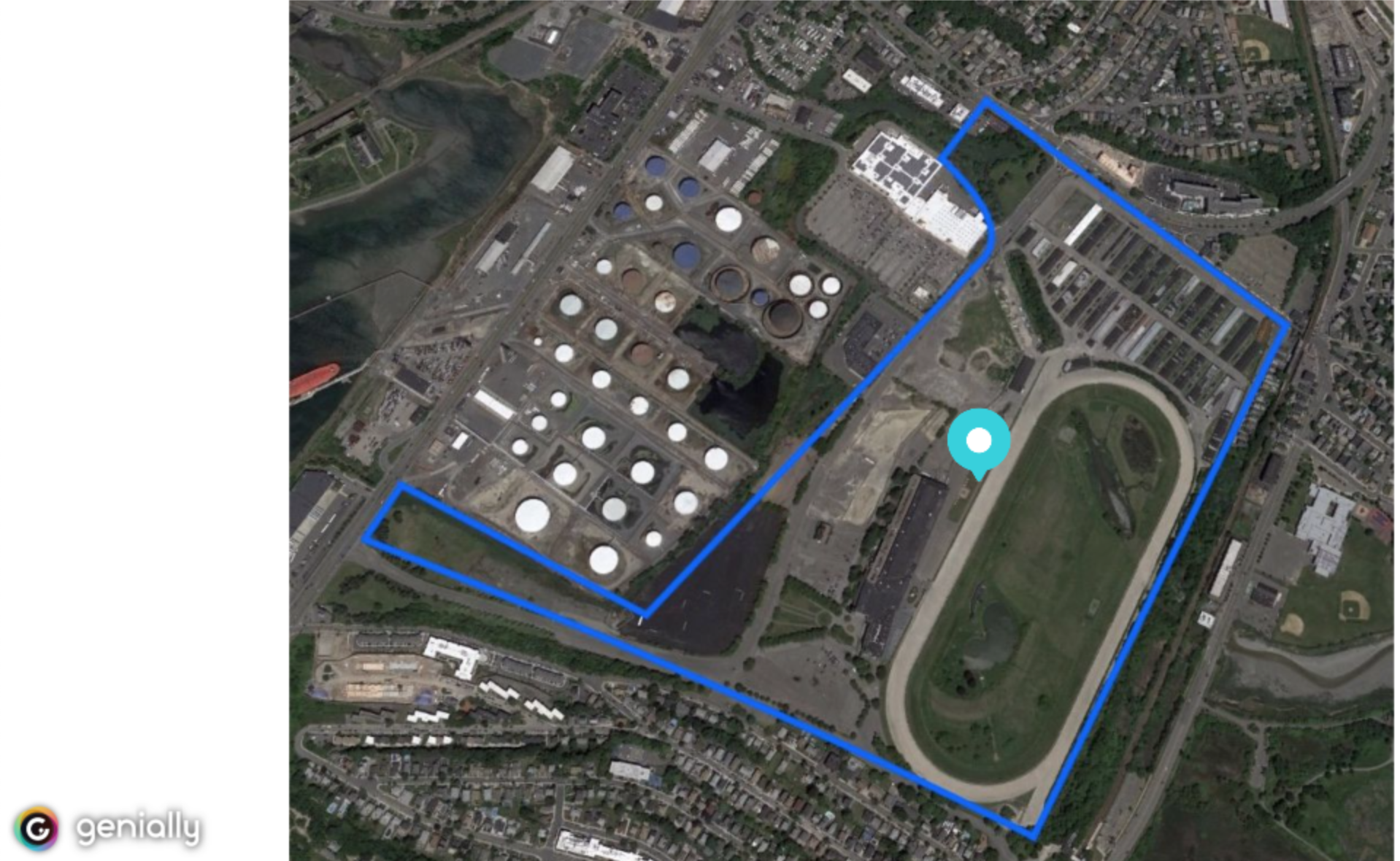

This new generation of councilors is pushing back against the old ways of doing business in Boston. The tension and dynamics of change is on full view around the development of the Suffolk Downs Racetrack property, a 161-acre parcel of land that straddles East Boston and Revere.

HYM Investment Group has purchased the land and is hoping to build some 10,000 apartments and condominiums, along with office space for 25,000 workers. Edwards and her community do not want a second Seaport District in their backyard, yet, another sub-neighborhood designed for outsiders to settle in East Boston.

Edwards points to the way in which HYM Managing Director, Tom O’Brien, is repeatedly interviewed by the media as inappropriate and emblematic of an overly cozy relationship that has always existed between developers and Boston City Hall.

“I think when you choose to talk to Tom, or any developer about the other side, it elevates them whether you mean to or not,” said Edwards. “It’s as though they're at the same level and impact and influence [as a city councilor].”

Edwards does not think that O’Brien is going to bring a different way of doing things just because he used to be on the inside of the process as the head of the Boston Redevelopment Authority (now the Boston Redevelopment & Planning Agency).

HYM Investment did not wish to comment on Edwards’ statements.

In addition to fighting back on the Suffolk Downs redevelopment process and plans, Edwards has proposed that the Zoning Board of Appeals (ZBA) be completely overhauled and replaced with a transparent process that includes members of the neighborhood communities who are most impacted by development.

[1] Awards include: Affordable Housing Finance Magazine's 2006 Reader's Choice Award for the Nation's Best Housing Development; NAMHA’s 2008 National Award for Best Turnaround of a Troubled Property; 2009 Terner Prize for innovation and leadership in affordable housing.

POV: Keni Nguyen

Inside Clipper Ship Wines

Keni Nguyen does not live in East Boston, but he knows East Boston.

Nguyen is the owner of Clipper Ship Wine & Spirits, a large liquor store located in Maverick Square, the heart of East Boston. He was 5 years old when his family moved from Vietnam to the United States. He has run the family business for 20 years.

“The [city government] doesn’t know the city like business owners,” Nguyen said. “They don’t know what is behind closed doors.”

For 20 years, Nguyen has seen buildings rise, people move in and people move out. His clientele has changed and his merchandise has been adjusted. More recently, his sales have declined.

When Clipper Ship opened, Nguyen remembers a booming business.

“There used to be a big Latino community,” he recalls. “Business was good when they were here. Spanish [speakers] helped the business grow. Nobody parties like the Spanish [speakers]!”

“Now, the community is mixed,” he said. “There are a lot of white people.”

Business has changed for Nguyen. He says the new demographic in East Boston -- more affluent -- buys one or two bottles of wine, and don’t return to the store for a month. That’s a big difference from the Latino community.

So where are the Spanish speakers?

Nguyen believes that the Latino community is being pushed out by high rent prices.

“They don’t want to leave,” he said. “But they are being forced to.”

The past 20 years have been revolutionary for East Boston. The past five, crucial. Concrete has flooded the neighborhood in the shape of new development.

Change is inevitable for East Bostonians, from residents to business owners. The sound of construction machinery has become mundane in the neighborhood. The constantly-changing customer demographic has been adapted by businesses.

And Keni Nguyen has had some trouble adapting. Clipper Ship used to be one of the only places to get liquor in the neighborhood. Now, more development means more houses, more houses mean more stores, and more stores mean more liquor permits. More liquor permits mean more competition for Nguyen.

However, he remains positive. He came to the United States to live the American Dream. His family opened a liquor store in East Boston and proved it was possible. And now, amid change, he’s pushing through.

“We’ll handle it,” he said. “That’s what we do for a living.”

POV: Residents of East Boston

Vox Populi

Suffolk Downs: A New Neighborhood on the Rise

The final day of live racing at the former thoroughbred racetrack in East Boston was June 30, 2019.

Built by 3,000 workers in just 62 days, Suffolk Downs Racetrack opened in 1935 and gathered the best in thoroughbred racers, including Seabiscuit, Whirlaway, John Henry, Cigar and Skip Away.

After several failed plans for development, including a bid to serve as Amazon’s second headquarters, the land was sold to HYM Investment Group for $155 million dollars in 2017.

HYM has proposed a massive development that will include housing, offices, and stores, similar to their other projects at Boston Landing and Assembly Square, located in the Greater Boston area. In the case of Suffolk Downs, however, HYM plans to include large areas of open, green space for public use.

Though still awaiting final approval from the City of Boston, the creation of a brand new neighborhood at the Suffolk Downs site will have significant impacts – both good and bad – on the working class neighboring towns of East Boston and Revere.

Considered the “last frontier” of open space for development in Boston, what was once a magnet for horse lovers and gamblers will again provide a new place to congregate in the ever changing dynamic of urban life.

Project Team: Ophelia Adjei-Awuah, Sara Amell, Ryoma Komiyama, Sophia Nadwani Krupnik, Rachel Rock

Executive Producer: Professor Michelle Johnson