In a little over a year, COVID-19 has infected more than 150 million people, and claimed the lives of over 3 million worldwide. The pandemic and its devastating effects have made horrific headlines for months: sickness, hospitalizations, ventilators, death. But, there is another aspect of COVID-19 that has drawn fewer headlines, and as a result, many have suffered in silence in the isolation of their homes, experts say.

Some of COVID-19's symptoms, such as shortness of breath, fever, cough, and oxygen deprivation, are easy to spot. Others are not. The virus does not just affect the body - it affects the mind, too, research shows. Forced lockdowns, quarantines, remote learning, and working from home have caused a wave of anxiety and depression amongst people across the U.S. and around the world.

A report from the Kaiser Family Foundation shows how the pandemic has negatively impacted the mental health of Americans. The results of the analysis indicate that four in 10 adults have reported symptoms of anxiety or depressive disorder, up from one in 10 from 2019.

Since April of 2020, Massachusetts has seen a steady increase in reported symptoms of depression and anxiety among adults. Struggling with their mental health, more and more people have turned to resources such as therapy, suicide hotlines, and hospitals.

Just as nurses and doctors have led the fight against COVID-19 in hospitals, there are other frontline workers playing their part to help those struggling mentally: therapists, psychiatrists, social workers, and advocates.

These are some of the stories of Boston's mental health workers.

As a sophomore in high school, Thanh Phan was in an accident and suffered a small brain injury. Little did she know that this incident would lead her to her passion, and eventually her career.

“I remember that time, it was very tough for both my parents and myself. I just remember (thinking) like, 'I wish I could go into a field to understand the brain and human connection more."

As a result, Phan decided to major in neuroscience, on her way to fulfilling her wish to learn more about the human brain.

In college, Phan was the person friends constantly came to for advice. They were "always like in the dorm, just coming in to talk," she said. This happened so often that one day, her roommate suggested that she should go into psychology. It was a path Phan had never considered.

“Given my culture, behavioral health and mental health are very stigmatized, so my parents weren't so fond of the field," she said.

She also said, "in Vietnam, particularly, mental health is not really well known or as developed. And there's the saying always that, you know, 'when you work with the crazies, you become crazy.' And I think that perception, that mental health is for the crazy people, is put often in media and things like that. There's that false perception."

Although she faced cultural judgment and false perceptions, Phan entered a psychology program and jumped right into the field. Once her parents saw her passion, and the work she was doing for the community, they immediately supported her career shift.

This is where Phan is today: she is a fourth-year doctoral candidate at King's College and a psychology intern at Harbor Health Community Center. As an intern, she actually gets to see patients herself.

"My favorite part is just getting to be with people on their journey," Phan said. "Just being able to sit with them, listen to them, and just kind of be that person to be supportive, that not a lot of people can say they have that in their lives. I think that human connection is something I really love."

Phan's job changed drastically when COVID-19 hit Boston in March of 2020. The nature of her day-to-day changed dramatically, as therapists all over the world shifted to telehealth, meeting with patients online. Thanh admitted that switching from face-to-face counseling to online talks was a challenging experience. Although she misses sitting in a room with patients, she is able to see the positive side of telehealth for her patients.

“I do have to say even though it’s not the same, that interpersonal connection, I do think for a lot of people this is a lot more comfortable for them; more ease of access. Some people are self-conscious and don’t want to go out; it’s easier for them to access the care at home,” Phan said.

COVID-19 not only changed how Phan is able to see her patients, but also what her patients talk to her about. Since she's fluent in Vietnamese, she is often referred patients who also speak the language. As part of the Asian community, she understands cultural norms and nuances that someone outside the community may not. As a result, many of her patients have expressed an anxiety that the pandemic has brought forward: hate crimes against the Asian community.

“My patients are just afraid to go out, even on the bus. I personally know people who have been attacked, and it is hard, as a clinician,” Phan said.

Following the fear of the pandemic, a series of racial attacks against Asian populations has taken place in the U.S. According to STOP AAPI HATE, there have been more than 6,603 reported cases of racist attacks on Asian people, and among them, elderly Asians made up the majority of the victims in the past year. According to Phan, more and more of her Asian patients started to fear that they would be attacked when going out, giving her and other therapists a heavy workload to help them address their feelings.

"As a clinician, when you hear an attack you think, 'is that my client? Is that my client's family? And, you know, no one should have to go and worry about that, right? Or like, go to bed worrying about their safety, or thinking about, like, waiting for the bus, like someone's going to attack them from behind. So it's been tough," Phan said.

Phan also said that her younger patients are afraid of going back to school. They do not know if they will have support from peers and teachers.

Difficulties have also arisen from the cultural perspective. Some in the Asian community may be reluctant to talk about mental health issues. Therefore, Phan explained, helping them to understand mental health issues has become part of her job, too - which starts with accessibility.

According to Phan, mental health resources in Massachusetts lack accessibility, especially for those who have limited English language skills.

"I do think we can be better in terms of having additional resources for marginalized groups, for example, just translated questionnaires if you're doing assessments ... info sheets on depression for groups, like the Vietnamese population, to actually understand what it is and provide that psychoeducation piece," Phan said.

During the pandemic, Phan has volunteered to translate documents for Massachusetts General Hospital, wishing to help patients with various language backgrounds understand mental health better.

When asked about advice for people going through mental health issues, Phan said they should not hesitate to speak up and seek help.

“The first step is talking about it, and leaning in for support,” Phan said, "because you should not have burden it alone. Connect with the people around you.”

Thanh Phan. Photo by Nicole Avazian

Thanh Phan. Photo by Nicole Avazian

Protesters holding banners at a Stop Asian Hate rally in Boston. Photo by Mutian Qiao

Protesters holding banners at a Stop Asian Hate rally in Boston. Photo by Mutian Qiao

Amy MacDougall knew that her mother was a great listener.

Her mother, Carol Lockwood, was one of the first Samaritans in Boston: a volunteer on their suicide prevention helpline. She always made sure to carry home the lessons she learned on the job.

“Growing up, we always talked about suicide as a very non-judgmental, normal thing,” said MacDougall. “She was certainly the mom in my neighborhood that all my friends and all my brother’s friends wanted to talk to.”

Lockwood was a friend, a good listener, an empath. Without even realizing it, she continued her work long after her shift was over. For MacDougall, at the time it wasn’t easy to understand, but now she says everything is a lot clearer.

“She was incredibly understanding as a mom growing up,” MacDougall said. “That explains to me now why she was the most popular mom among my friends.”

MacDougall's mother passed away more than 20 years ago, but her legacy lives on in her daughter, who is now a volunteer and leader herself at Samaritans. The non-profit organization offers several suicide prevention services to residents in the Greater Boston area, such as a 24/7 helpline, grief support services, and community outreach services.

“It’s kind of nice to get involved in that work now and look back and see from that perspective, I can understand now how [my mother] brought all those skills to parenting,” MacDougall said. “It honors her memory.”

While MacDougall's been familiar with Samaritans since she was younger, she only formally became involved with the organization in her 50s. Before that, she was a social worker for several years, working with court-mandated clients. While she enjoyed social work, MacDougall said at one point she realized she was losing her empathy. She knew then she needed a break and a change, so she volunteered for Samaritans in 2017.

She never went back to her old job.

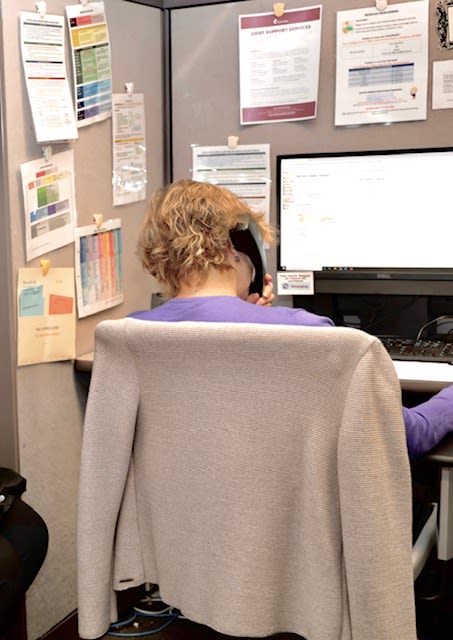

As a volunteer, MacDougall is responsible for answering calls to Samaritan's 24/7 helpline. In her role as a home leader, she offers support to other volunteers and serves as a supervisor.

"It’s like walking in a room," MacDougall said. "You walk in, you offer your support, and then you make sure you walk out."

Her main job is listening. There is no judgment, no offering solutions, no input. Simply being there for someone.

Listen: MacDougall Describes Her Work

“I’m not there to fix their problems, I'm not there to solve anything, they’re a stranger. I'm just there to verbally put a hand on their shoulder and say, ‘I’m here, I hear you, I can hear your pain.’ And then I move on to the next person.”

The arrival of the pandemic to Boston in March of 2020 forced the organization to move online. With Samaritans going remote, there was an influx of volunteers from all over the world, which meant better coverage of shifts and more availability for callers.

The pandemic, however, also meant more callers. With anxiety and mental health disorders increasing, more people turned to the helpline.

“It was a tough winter,” MacDougall said. “This winter was much harder for people.”

For the first time, callers shared similar experiences, anxieties, and worries - all brought together by shared trauma.

In particular, two groups stood out to MacDougall in the fall: students and the elderly. Two groups with little in common echoed a shared fear of isolation and paralyzing anxiety for the future.

A College Pulse survey commissioned by Course Hero and the National Association of Student Personnel Administrators found that nearly 1 in 5 students reported being “constantly” anxious about the pandemic. 3,500 full-time college students were surveyed between September and October 2020, and 56% of them reported being at least “somewhat anxious” about COVID-19.

This anxiety was reflected in calls to the Samaritans helpline.

"So many students, especially freshmen, who were back at college or going to college for the first time, that were so isolated,” MacDougall said. “They didn't wanna tell their parents, they didn't wanna go home. They were just trapped in this room.”

Similarly, the older population living in senior centers found themselves deprived of many of the activities that used to fill their days and deprived of the human contact they were accustomed to.

Listen: What's Next?

“That was incredibly isolating for this whole group of people,” MacDougall said. “They would walk around the neighborhood or they would go to the library, to the police station … all these people they talked to every day, all gone. They were feeling incredibly isolated, and distressed, and out of touch.”

Another common anxiety that has stood out throughout the year is worry about finances, with layoffs, evictions, and financial losses escalating.

“We're always here to listen and that's all we can do,” MacDougall said. “If you didn't have your friends to talk to or you didn't have your family to talk to, or you couldn't talk to them about something, that's who you would call: the Samaritans. And they will listen."

Amy's mother Carol Lockwood circa 1995. Photo courtesy: Amy MacDougall

Amy's mother Carol Lockwood circa 1995. Photo courtesy: Amy MacDougall

Amy MacDougall answering calls in the Samaritans Boston office. Photo courtesy: Amy MacDougall.

Amy MacDougall answering calls in the Samaritans Boston office. Photo courtesy: Amy MacDougall.

“My story thankfully has a happy ending, but not everybody is able to share their story. I am just really happy to be able to share a story that allows people to think differently, and allows them to take the initiative to prioritize their mental health," said Nieisha Deed.

This story, Nieisha Deed’s story, is one she has told many times - to individuals, to crowds, and more recently to online audiences. Deed is the founder of PureSpark, a mental health organization that aims to spread awareness, educate, and provide access to resources. The idea for PureSpark came from Deed’s own struggle with mental health, which culminated in an attempt to take her own life in 2017.

Listen: Deed's Personal Journey

PureSpark uses social media and their website to provide resources and daily coping mechanisms that would otherwise be out of reach for someone who is unfamiliar with the mental wellness system. While open to providing information for everyone, the organization’s focus is on Black women. They started a Massachusetts wellness directory this year.

After graduating from Howard University in 2005, Deed worked as an accountant for 15 years. She changed paths after her struggle with mental illness. She left her apartment in Washington, D.C., behind and moved back home with family leaving her old career behind. This was not an easy, or conventional choice, but Deed knew she needed the change.

“Doing things that are not good by societal standards, but are good for you, are important," she said. “It is just what you’re prepared to do and how bad you want it.”

Deed first publicly shared her story at McLean Hospital in Massachusetts. This step sparked a new confidence in her, that she no longer needed to be afraid of people's judgments. She decided she wanted to keep educating people, so she started a social media campaign to continue spreading her message. “I learned what depression is and how healing takes place, and I wanted to share this with the world," she said.

COVID-19 arrived shortly after PureSpark officially took off. As a result, many of her plans had to shift to a virtual format. This included Peer Support by PureSpark, a weekly support group where people could come in, talk about their feelings, and learn different methods to cope with them. The timing with COVID-19 ended up working out. “I started a virtual group to discuss our concerns, the existing racial tensions, and how we can mentally cope,” Deed said. The ultimate goal of Peer Support is to educate people on the various ways they can deal with feelings of depression or anxiety.

A lot of people didn't know where to begin. “They did not know the difference between a therapist and a life coach," Deed said, "and that is where I came in.”

The COVID-19 pandemic has been disproportionately affecting communities of color. A study conducted in Massachusetts found that communities with higher percentages of Black and Latino populations registered higher rates of COVID-19 cases. Nationwide, the COVID Tracking Project has found Black people have died at 1.4 times the rate of white people in the U.S.

Deed expressed a deep concern: that there are not enough resources out there, especially focused toward People of Color.

“There are not enough experts who are culturally competent to deal with the trauma associated with Latin, Asian, and African history," she said.

In addition, she said there are currently not enough therapists in general. “There are immense waitlists out there and if it's urgent, one cannot even get a therapist,” she added.

In Peer Support, she has seen many attendees who are frustrated because of the pandemic and the isolation that it has caused. “Many women with children have turned into teachers. They come to us for help, asking how they are supposed to teach, do household chores as well as work," Deed said.

She also noted that people who are single and do not have children are facing even more extreme isolation. “They cannot go outside, and Zoom cannot replace real human connection," said Deed.

Another topic that has been discussed in Peer Support is the racial tensions that escalated this past summer. Deed was around 10 years old when she saw Rodney King beaten on television, and she said that the killing of George Floyd brought back that trauma.

Listen: Impact of King, Floyd

Deed said that at one point, she stopped watching the news because it was bad for her mental health. Instead, she felt like she needed to do something about it. “I needed to have a space for people who look like me and give them a chance to share their stories and feelings," she said.

Deed's advice to people struggling with mental illness is manifold. First, she points to the need to realize that people are not alone and that they can adapt. For instance, they can have small, socially distanced get-togethers and Zoom parties. She added that if one is having a tough time, it's essential to stay connected to family and friends. “This time has taught us how important relationships are," she said. "Feel your feelings, and find ways to cope.”

Jason Strauss always pictured himself as a doctor throughout his life. Yet psychiatry was not the first field he had in mind.

"I thought I was going to maybe be a pediatrician or an internist or when I was doing my rotations in medical school, I just really liked being able to spend a significant amount of time with my patients and really getting to know them," said Strauss.

Strauss is the Chair of Psychiatry at St. Elizabeth's Medical Center, where he specializes in treating patients with severe and persistent mental illness. He is also responsible for the training of other psychiatrists.

He was first exposed to the psychiatry field when he began treating elderly residents and found to his delight that it was a pleasure working with them. Following his residency work, he began a fellowship in geriatric psychiatry for a year. Then, for the next 12 years, he worked as a geriatric psychiatrist in several settings.

Nine months ago, he transitioned to his current position, and while he still works with older patients, he has also been working with underserved populations.

"I sort of felt like in my role, and kind of doing teaching and training and sort of having some oversight over our department and what our goals or priorities should be, it just sort of felt like this was a new and interesting challenge," he said.

The coronavirus pandemic changed the dynamics in hospitals and Strauss has been a witness to a lot of these changes.

"As the pandemic progressed into the summer, and fall and even more so, this spring, things have really taken such a turn for the worse in terms of people's mental health," Strauss said.

"Just the isolation, not being around people, not being able to be outside, and not being able to engage in activities that are generally enjoyable."

The pandemic has even taken a toll on those who previously did not have any mental health issues. Usually healthy people found themselves seeking treatment for the first time in their lives, completely overwhelmed by the pandemic, according to Strauss.

"We're seeing a lot of people in our outpatient clinic who really don't have a past psychiatric history, but are really struggling a great deal with depression with anxiety, for the first time and they've dealt with a lot of stressors in their lives," said Strauss.

While on one hand, the pandemic affected people with no previous history of mental health issues, on the other hand, it also exacerbated problems among those who had existing conditions, according to Strauss.

"What we're seeing is people are much sicker," Strauss said. "People who do have a history of mental illness, it's really made their symptoms much worse. And it's exacerbated their underlying illness.

"It's affected, in many cases, their ability to seek treatment. It's affected their ability to be on the right medication if they need it, or the right kind of psychotherapy if they need that," said Strauss.

This higher demand for help strained hospitals' resources. Even at St. Elizabeth's, Strauss said, more patients needing assistance meant fewer beds and longer waitlists. Additionally, Strauss pointed out that with nursing homes closing to new patients, those who would typically live in nursing homes are forced to remain in the hospital.

"People who would ordinarily be able to be discharged safely to nursing homes, are just not able to because the nursing homes are not accepting patients and so patients are not safe to go home. And so they stay in the hospital," Strauss said.

Substance abuse is also an issue that has grown during theCOVID-19 pandemic, said Strauss. Stress and the difficulty of managing life in a pandemic have played significant roles in that matter, increasing the rates of alcohol and opioid use.

"We are seeing people who have been struggling for years, and people who had maintained many years of sobriety who have relapsed under the stress and difficulty of the past year," said Strauss.

"We've seen many people who really didn't have any significant past history, who are really struggling for the first time and seeking treatment for the first time."

Strauss does believe the numbers will go down at some point. Still, given the current state, it may be difficult to give an exact estimate of when that will happen as a majority of individuals are "collectively traumatized" from all the shared experiences from the past year, he said.

"As a society, we're just , you know, a very anxious society and there's just always a lot going on," Strauss said. "There's a lot going on in the news and there's a lot going on in politics and I think the struggles around that are going to continue to some extent."

Looking Forward

The COVID-19 pandemic has altered many lives: loved ones have died, jobs have been lost, and celebrations have been canceled. The world turned upside down in a matter of weeks and swiftly moved to adjust to a new reality.

Adapting has been easier for some than for others. Many questions remain as people struggle with their mental health and new anxieties about the future arise: Will there be another wave? What about new variants? When will the vaccine be available around the globe? Will we ever go back to normal?

Despite all the negatives the pandemic has brought on, there have been some positives that may carry forward.

COVID-19 forced Samaritans out of their office, which allowed the organization to take on remote volunteers, expanding their reach, according to Samaritan's Amy MacDougall.

“The training classes all of a sudden filled up like crazy, and now we can train people all over the world. We have people in India; we have people on the West Coast who can do some of the overnight shifts. It really gave us a whole lot more flexibility in terms of what we’re able to do, and the coverage we were able to have...our volunteer pool just bloomed,” said MacDougall.

More people have sought help for the first time, or accessed resources they might not have otherwise. PureSpark's Nieisha Deed has noticed this in the people who attend her Peer Support group.

“People are going to therapy for the first time in their life during the pandemic. 2020 really did bring a lot of attention to mental health,” she said.

Psychologist Thanh Phan agrees, as she has seen this first-hand in her practice as well.

“A lot more people are reaching out for help, and now I think it’s becoming a little more normalized with COVID. People are thinking ‘now I really need to take care of my mental health too,’” she said.

St. Elizabeth's Dr. Jason Strauss hopes that this increase in people seeking help will lead to larger conversations about the mental health system.

“I'm hopeful that there can be discussions about a reallocation of some of the resources so that you know there's more investment, and different care options and community options for people needing mental health services and treatment, because that's really the only way that we're going to be taking care of this population.”

Credits: Timeline information from NBC Boston; Background photographs in Mental Health Advocate section courtesy of Nieisha Deed; Photo of St. Elizabeth’s from Wikimedia Commons.