Social media may perpetuate political division, but it’s only part of the problem

Despite efforts to combat it, post-election misinformation persists

More than one month after Joseph R. Biden Jr. was declared the winner of the 2020 presidential election, social media is still being used as a tool for amplifying political misinformation. Continuous claims of voter fraud imply that supporters of President Donald J. Trump are among those at the forefront of driving misinformation campaigns on social media via hashtags such as #StopTheSteal and #SharpieGate.

On Nov. 4, just a day after the election, the Stop the Steal movement led to the forming of a Facebook group of the same name, aimed at pushing the narrative of voter fraud in favor of President Trump’s reelection.

The group attracted more than 320,000 members in one day, according to the New York Times, but within 22 hours, it was shut down by Facebook.

This response is one of many ongoing efforts of social media companies like Facebook and Twitter to combat election misinformation on their platforms. Twitter, for example, banned political advertising in October 2019 and has since been actively highlighting tweets containing misleading or false content.

A tweet by President Donald J. Trump on Nov. 5 that cited claims of voter fraud in the 2020 presidential election was labeled misleading by Twitter.

A tweet by President Donald J. Trump on Nov. 5 that cited claims of voter fraud in the 2020 presidential election was labeled misleading by Twitter.

In response, many Republicans and conservative Americans, including those who have had their social media posts labeled as misinformation, are moving away from mainstream platforms in favor of right-leaning outlets like Parler — a Twitter-like service that has reportedly drawn millions of users in November alone.

“Hurry up and follow me at Parler. I may not stay at Facebook or Twitter if they continue censoring me,” Fox News personality Mark Levin tweeted on Dec. 2.

Hurry and follow me at Parler. I may not stay at Facebook or Twitter if they continue censoring me. And one day I’ll have left their platforms. Parler is a wonderful alternative and is growing, and we need you there ASAP. It believes in truly open speech.https://t.co/3RnjMoknfj

— Mark R. Levin (@marklevinshow) December 2, 2020

A Pew Research Center survey conducted in July revealed that 64% of Americans — regardless of their political affiliation — think that social media has a mostly negative effect on the country.

Still, 78% of Republicans and Republican leaners expressed this concern compared to only 53% of Democrats and Democratic leaners.

The top reasons cited include misinformation, polarization, and the perception that these platforms oppose President Trump and conservative Americans.

The same dataset also found that more than half of Americans have become “worn out” by political posts on social media, with Republicans and Republican-leaning Independents being slightly more likely than Democrats and Democratic-leaning Independents to believe that social media “makes people think they are making a difference when they really aren’t.”

With the data suggesting a contrast to right-wing-led misinformation campaigns on Facebook and Twitter, there may be another factor at play.

Tommy Shane, Head of Policy and Impact at First Draft News, says the recent election misinformation on social media can be largely attributed to the president himself.

“The primary disinformation that occurred in the election came from the president with the effort to undermine trust in the electoral outcome in anticipation of losing the election,” he says. “That was the key disinformation campaign that occurred.”

Disinformation, unlike misinformation, is spread deliberately to mislead an audience.

In October, Harvard’s Berkman Klein Center for Internet & Society released findings from their study of mail-in ballot disinformation, revealing a similar conclusion to Shane’s that the president has, “perfected the art of harnessing mass media to disseminate and at times reinforce his disinformation campaign.”

“We should prevent [social media] from trying to be a useful tool, but it is not the cause,” Shane says, adding that social media is part of a larger ecosystem of tools that the president relies on to “mount a campaign of disinformation.”

Apart from social media, the Harvard study found that the president’s two other primary disinformation tools are television interviews on Fox News and press briefings.

“For reporters and journalists, the key thing is being wary of amplification,” Shane says, urging newsrooms — particularly local stations — not to air false messages without providing their own editorial perspective. “The press is a huge amplifier of information, so reporters and journalists need to be wary of how they are being manipulated for purposes of amplification.”

When the president addressed the nation on Nov. 5 during a press conference at the White House and claimed that fraudulent voting had occurred, ABC, NBC and CBS were all quick to cut away from his remarks, citing false claims.

Since the dawn of the COVID-19 pandemic, television news consumption has seen a surge in the United States, according to data from the Reuters Institute’s 2020 Digital News Report. As of April, it stands as the second most popular news source after online news.

Social media has also seen a surge in usage since the pandemic, with 48% of the population relying on it for news, though it trails behind television by over 10%.

The data also revealed that older Americans between the ages of 45 and 55 are most interested in local news and that younger Americans, namely between the ages of 18 and 24, are least interested.

“Age is a very significant predictor of vulnerability and that’s been put down to a combination of digital literacy skills but also high levels of trust, generally,” Shane says. “Often because older people’s networks are much smaller, and therefore, they’re more likely to seek information from trusted contacts, whereas younger [people] have larger networks, as well as being more digitally savvy.”

Some local news organizations have made an effort to educate their audiences on spotting disinformation and misinformation. Lisa Williams, Audience Engagement Editor at GBH News in Boston has been working on a new initiative called Internet Expert — an online game show that started in July to challenge contestants’ fact-checking skills in preparation for Election Day.

“People have to make decisions under pretty intense stress,” she says about voting. “I want to make sure that we’re informing them and not in a way that we are intentionally amping up the stress level.”

The game show featured seven episodes, each covering different topics on where election misinformation may arise, including campaign finance, voting, and manipulated media.

Despite not seeing it as a causal factor, Shane is still wary of social media’s role in spreading false information.

“One of the biggest [issues] around social media is labeling, the ways in which [social media companies] handled various claims in the days after the elections.”

In collaboration with four other researchers at Partnership on AI, Shane released a study in June that explored the ways in which misinformation labels on social media are designed, and the psychological effects they have on users.

Their study provided 12 design suggestions to help reduce the chance that a user would believe the labeled content. One suggestion was for misinformation labels to use more empathetic, non-confrontational language. For example, the phrasing “Rated False” is said to be more effective at convincing users that the labeled content is incorrect, as opposed to the “Disputed” tag used by Twitter, which risks presenting the issue as a mere difference of opinion.

Twitter labels some tweets containing false content as "disputed" and "misleading."

Twitter labels some tweets containing false content as "disputed" and "misleading."

But redesign efforts may not be enough of a response. Technology critics like Jaron Lanier argue that social media companies are built to profit off its users’ personal data, running on an algorithm that leverages targeted content to keep users on their app.

“Oftentimes when people think they’re being productive and improving society on social media, actually they’re not,” Lanier told Kara Swisher in a 2018 podcast interview.

“Because the part of the social media machine that’s operating behind the scenes, which are the algorithms that are attempting to engage people more and more and influence them on behalf of advertisers and all of this, are turning whatever energy you put into the system into fuel to drive the system,” Lanier adds.

Many Americans share this sentiment, with Pew Research Center reporting that 54% of Americans believe social media companies should ban all political advertisements and that 77% find it unacceptable that these companies would use their data to send targeted political content.

“You think you’re doing good with social media but behind the scenes, the manipulation engine is actually finding all the worst people and empowering them,” Lanier told Swisher.

Still, a significant percentage of Americans find social media to be a valuable tool for effecting political change.

A Pew Research Center survey conducted in September found that majorities of Republicans and Democrats — including Republican-leaning and Democratic-leaning Independents — feel that social media is at least somewhat effective in raising awareness about political and social issues. At the same time, the survey also reports that Democrats are more likely than Republicans to say so.

Bill Rieman, an Illinois resident who identifies as a Democrat, actively used Facebook as a tool to unite Democrats and Republicans to vote the president out of office. At 64 years old, he is motivated by the belief that both parties must work together to combat political polarization.

“I look at Facebook the same way as I do in a neighborhood,” Rieman says. “The people who are attracted to each other are each others’ friends.”

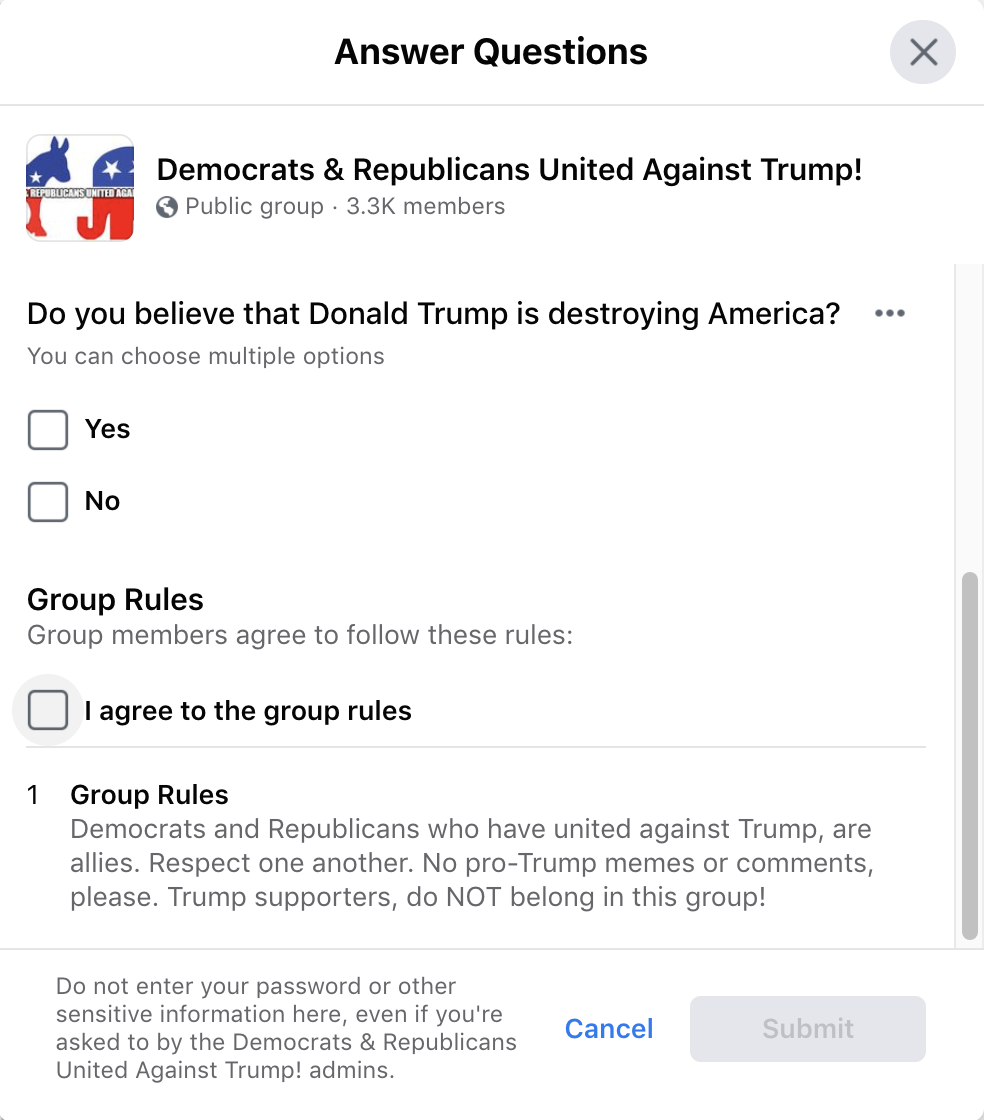

Since more than six months prior to Election Day, Rieman has served as a moderator for the Facebook group, “Democrats and Republicans United Against Trump!” As of December, its membership has grown to over 3,300.

The group describes itself as “an online community to unite regardless of political affiliations for the greater good of our country.”

Upon requesting to join, potential members are required to answer two questions, “are you in favor of removing Donald Trump,” and “do you believe Donald Trump is destroying America?”

“Basically, it's as simple as reading the title of the group,” Rieman says.

The Facebook group, "Democrats & Republicans United Against Trump!" requires users to declare their thoughts on the president before they can become members.

The Facebook group, "Democrats & Republicans United Against Trump!" requires users to declare their thoughts on the president before they can become members.

But he isn't the only one turning to social media in hopes of reaching out to Republicans to impact the election.

In March 2020, brothers Ben, Brett and Jordan Meiselas formed MeidasTouch — a political action committee that creates anti-Trump videos "with the primary goal of defeating Donald Trump in 2020," as the website states.

From the president's treatment of women to Vice President Mike Pence's frequent interruption of his opponent, Vice President-elect Kamala Harris, during the 2020 vice presidential debate, MeidasTouch's videos have criticized the Trump administration on various grounds.

The committee has over 91,000 subscribers on their YouTube channel and over 529,000 followers on Twitter.

Just one day before the election on Nov. 2, MeidasTouch released a video urging Republicans to choose "country over party" by voting against the president.

On Nov. 2, MeidasTouch published a video urging Republicans to choose "country over party" by voting against President Trump.

Some Republicans are also using social media to counter the president.

The Lincoln Project, founded in December 2019, is a Republican-led political action committee, aimed at preventing the president's reelection. Its founders include Rick Wilson, a long-time commercial producer for the Grand Old Party.

"The idea that social media is predominantly misinforming people is not true, lots of people find lots of value," Shane says. "Lots of people are skeptical but it doesn’t mean they're not getting important information."

Though activists and critics like Lanier are urging social media companies to restructure their advertising-dependent business models, Shane does not think users need to walk away from social media as a response to misinformation issues.

Instead, he advises users to practice questioning their emotional response to what they see online before sharing it with their followers.

“So often, the important thing as well as thinking “does this seem realistic and plausible,” is asking, “how is this making me feel?””